for Sonja Landweer

Sonja Landweer (born in 1933 in Amsterdam, died Dec 2019) was a Dutch artist resident in Ireland from the late 1960s. She created ceramics, jewellery and sculpture exhibiting in Ireland and internationally. She and Seamus Heaney shared a mutually inspirational friendship over many decades.

Heaney composes a poem with her in mind celebrating inventiveness, originality and indomitable human spirit. He appends his own two-part version of a poem written by a Dutch poet J. C. Bloem who describes the agonies of nazi occupation of Holland in WWII and the need to win the peace.

Heaney’s epigraph might well have fitted the Programme of the joint exhibition he and Landweer put on in Kilkenney entitled ‘Out of the Marvellous’. His blending of ceramic and poetic processes acknowledges that successful creativity transforms basic ingredients into works of art.

He imagines a visit to a potter’s workspace (we know that Heaney was familiar with Landweer’s studio).

The artefacts in this store (strongroom of vocabulary) are akin to the lexis the poet has shaped and drafted (where words like urns that had come through the fire) then set on one side (bone-dry alcoves next a kiln) awaiting the next move in the poetic ‘glazing’ process.

Transformations brought about by the kiln’s heat (came away changed) leave the creator as dumbfounded as the sentry who witnessed Jesus’ resurrection (guard who’d seen the stone move) in the heat of the moment (diamond-blaze of air) or in the same way that pleasing objects or poems of genuine quality (gates of horn) are the product of the humblest of ingredients( behind the gates of clay).

- the image of ‘gates of horn and ivory’ that are mentioned in both Virgil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Odyssey appear to distinguish between true dreams and false; the phrase originated in the Greek language, in which the word for “horn” is similar to that for ‘fulfil’;

I

A junior pedologist on the road to discovering the raw material of pottery.

Heaney’s roots lay deep in the Irish landscape. The peaty bogland around his childhood home was deep brown in colour (the soils I knew ran dirty) hinting also, perhaps, at ‘tainted’ sectarian activities in Northern Ireland.

His interest in natural textures and types began in the clear-flowing Moyola close to home in Castledawson (river sand), not immediately suitable for pottery (stayed itself) but describable in onomatopoeic assonant terms – slurpy (slabbery) and glutinous(clabbery) in adverse weather conditions (wintry, puddled ground).

As young Heaney’s horizons widened he came across a larger river and a different, more plastic substance (Bann clay) with shine (wet daylight) and clinging richness (viscous satin) concealed beneath the river bed’s top covering (felt and frieze of humus layers).

A richer form (true diatomite) took even more finding (within a poetic dynamic of touch and pressure – little sucky hole). Heaney sets out its other properties: distinctive colouring (grey-blue), ‘eggshell, finish (dull-shining), lack of smell (scentless) and solid substance (touchable).

To Heaney’s young senses this seemed soothingly primordial (old ointment box, sticky and cool).

At that same moment Sonja Landweer was swimming off the Dutch coast (by the Norder Zee), a light-bathed mythical creature of the sea itself (luminous with plankton … nymph of phosphor). In a frolic of free imagination he translates Sonja into a virginal priestess (vestal) waiting on the goddess Pottery-Sand (Silica) working on the firing line (under grass and glass and ash) in the land of Kiln (fiery heartlands of Ceramica).

Had their paths crossed then they might have played together in a child’s elemental make-believe world (cold gleam-life under ground and off the water), birds of a feather (Heaney finds a rich alliteration) doing what children do (weird twins of puddle, paddle, pit-a-pat). They might well have disregarded parental warnings (the small forbidden things) to stay clean (worked at mud-pies) or take care (too high on swings) even experimented with their innocence (played ‘secrets’ in the hedge or ‘touching tongues’).

There was a reason why this never happened (in the terrible event): nazi blitzkrieg (night after night) and Sonja’s personal exposure to death (you watched the bombers kill).

As a gift to creativity (heaven-sent) Sonja emerged (came backlit) from the explosive backdrop of conflict (fire, through war and wartime) to create her own enduring legacy (ever after, every blessed time) visible through her pottery (glazes of fired quartz and iron and lime).

Heaney creates a syllogism from something she said in relation to her trade – if glazes, as you say, bring down the sun then this links inversely with the clay it takes to make her pots (your potter’s wheel is bringing up the earth).

The kiln’s magma-like heat that fires each artifact leads to a newly coined cry of adoration: Hosannah ex infernis for heat turned to good effect (burning wells) and natural pottery ingredients (Hosannah in clean sand and kaolin).

Heaney’s coda borrows from the poem he will translate in the final couplet (‘now that the rye crop waves beside the ruins’) with its tell-tale signs of a recovering world (ash-pits, oxides, shards and chlorophylls).

- slabbery: Heaney creates an adjective imitatitve of ‘slobbery’; the word compares with the Germanic/ Frisianslobberje “to slurp,” Middle Dutch offers overslubberen and slabberen.

- clabbery: adjective suggestive of ‘muddy’ 1824, from Irish and Gaelicclabar “mud.”

- puddled: from 15th century the verb means ‘to dabble in water, poke in mud’;

- Bann: (Irish an Bhanna meaning “the white river’) reference to the longest river in Ulster, 80 miles (129 km) long, winding its way from the southeast corner of Northern Ireland to the northwest feeding into the enormous Lough Neagh en route;

- diatomite: diatomaceous earth produces the skeletal remains of single celled plants called diatoms, hence the name diatomite. These microscopic algae have the capability of extracting silica from water to produce their skeletal structure. When diatoms die their skeletal remains sink to the bottom of lakes and oceans and form a diatomite deposit;

- sucky: an adjective coined to conjure up sound and touch;

- plankton: organisms that live in water and provide a crucial source of food to many fish and whales; plankton is made up of tiny plants calledphytoplankton and tiny animals;

- phosphor: solid material that emits light, or luminesces when exposed to radiation such as ultraviolet light or an electron beam ;

- Norder Zee: Dutch for North Sea;

- vestal: in ancient Roman religion the Vestals or Vestal virgins were priestesses of Vesta, goddess of the hearth. They cultivated the sacred fire that was not allowed to go out. Heaney’s invented goddess is appropriate to pottery themes of the poem, borrowed from the word for ‘sand’;

- Silica the goddess bears an appropriate but adapted name; Ceramica is based on the term for ‘pottery’;

- pit-a-pat: with a sound like quick, light steps;

- glazes: vitreous substances used to coat pottery before it is fired in a kiln: quartz, iron and powdered limestone are presented as ingredients;

- fired: baked in a kiln ;

- Hosannnah ex infernis: a neat reversal of the Biblical shout of adoration, from ‘hosanna in excelsis’ (Glory to God in the highest) to ‘Glory (to pottery) from underground;

- kaolin,also called china clay, soft white clay that is an essential ingredient in the manufacture of china and porcelain; it owes its name to Kao-Ling a hill in China;

- shards: broken pieces of pottery or glass;

- chlorophylls: reference to green pigments found in algae and plants. These extremely important biomolecules are critical in photosynthesis, which allows plants to absorb energy from light.

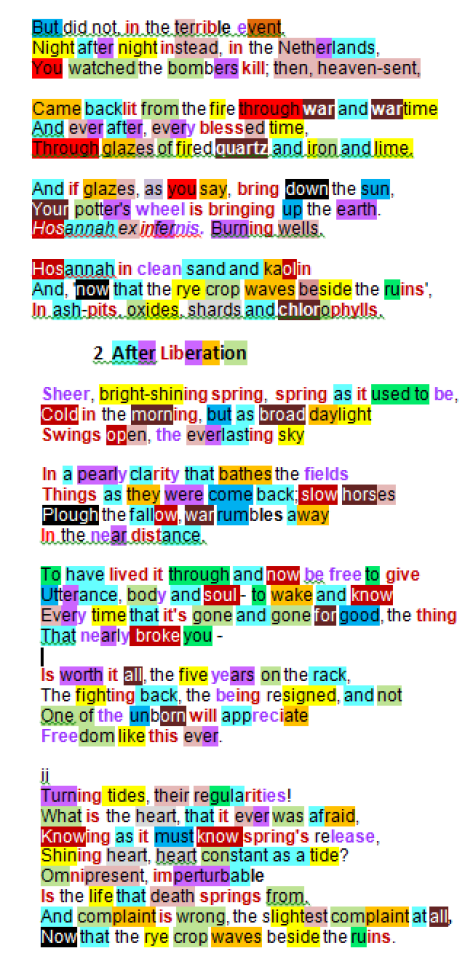

2 After Liberation

i

Bloem’s lyric celebrates returning nationhood: the unmitigated beauty of the world around (sheer, bright-shining spring, spring) re-found (as it used to be) … dawn chill followed by an opening door (broad daylight swings open) across Holland’s huge flatland (everlasting sky) all the more appreciated by those who have come through (marvel to survivors).

Bloem is soothed by pale elemental promise (pearly clarity that bathes the fields) of incoming freedom (things … come back), the farming calendar picking up again (slow horses plough the fallow) despite the fading reminders of conflict.

The joy of survival and freedom of expression are foremost (utterance, body and soul). Realization that the spirit-wrecking ordeal (thing that nearly broke you) is over is worth repeating and repeating (gone and gone for good). During the long ordeal (five years on the rack) Dutch spirit never ceased (worth it all) to resist (fighting back) or turn the other cheek (being resigned).

Ironically the sheer exhilaration of the moment (freedom like this) will never be fully understood by future generations (not one of the unborn will appreciate).

ii

Given that Earth’s gyres deliver predictable continuities (turning tides, their regularities!) why then is the human psyche ever riven with anxiety (what is the heart, that it ever was afraid) why does its inner glow (shining heart) not appreciate that the good times will return (spring’s release), that what goes round comes round (constant as a tide).

Given life’s precarious status (life that death springs from) humanity is enjoined to seize the very best from what it is presented with (omnipresent, imperturbable).

This will need to include the further compromises required for reconciliation (complaint is wrong, the slightest complaint at all)). Just take, Bloem suggests, at the irrepressible recovery of nature as your template (now that the rye crop waves beside the ruins).

Bloem points a way ahead for the embittered Dutch nation in 1945. People hostile to each other were called upon to sit around the same table and agree to co-manage the future. Perhaps the Northern Irish too can hope that after decades of death and revenge the cessation will lead to a permanent peace. Heaney understands only too well that entrenched views will have to be set aside before the permanent peace of the Good Friday Agreement two years later may become a reality.

- C.Bloem (1887-1966): highly regarded in Holland as a lyric poet, ‘minor’ only in the sense of his limited output;

- fallow: land that has lain for a period without being sown in order to restore its fertility; in this case war interfered with the normal farming calendar;

- rack: literally an instrument of torture consisting of a frame on which the victim was stretched by turning rollers to which the wrists and ankles were tied; metaphorical reference to years of suffering under Nazi occupation;

- regularity: Heaney applies the word to a maritime phenomenon that follows the rules of physics and can be forecast to the second; sunrise, lunar eclipse and the movement of the sea’s tides are all examples of consistency;

- omnipresent: widespread, everywhere;

- imperturbable: calm, hard to upset;

- Bloem’s tribute to the human spirit it offers interpretations that point to the same end: all bad things come to an end in the ebb and flow of life; change for the better is predictable; the timid heart will finds a way to resist the might oppressing it and relish being free;

- NC refers to Heaney’s translation of ‘After Liberation’: ‘a post-war poem of endurance, survival, constancy and renewal by the Dutch poet J. C. Bloem’ (p189);

- a section of Bloem’s original poem Na de bevrijding reads:

Schoon en stralend is, gelijk toen, het voorjaar, / Koud des morgens, maar als de dagen verder/ Opengaan, is de eeuwige lucht een wonder/ Voor de geredden./ In ‘t doorzichtig waas over al de brake/ Landen ploegen weder trage paarden/ Als altijd, wijl nog de nabije verten/ Dreunen van oorlog./ Dit beleefd te hebben, dit heellijfs uit te/ Mogen spreken, ieder ontwaken weer te/ Weten: heen is, en nu voorgoed, de welhaast Duldloze knechtschap -/ Waard is het, vijf jaren gesmacht te hebben,/ Nu opstandig, dan weer gelaten, en niet/ Eén van de ongeborenen zal de vrijheid/ Ooit zo beseffen. …. En de kleinste klacht schijnt nauwlijks hoorbar,/ Waar rogge om de ruines groeit./

Comments made by Irish poet Eamonn Grennan about Seamus Heaney’s final collection, ‘Human Chain’ (2010) have a particular resonance: … ‘the poet, like a master potter, slowly shapes on his word wheel the given clay into a vase, an urn, a bowl and … glazes it with living colour’ .

- the epigraph comprises two tercets in a single sentence; 1 has eleven tercets of 15 sentences; 2i comprises four quatrains in three sentences and 2.ii two quatrains in four sentences;

- Heaney’s epigraph and his poem are based around a line length of ten syllables; the poem follows a rhyme scheme, at first regular axa/ byb/ czc etc but varied in the last six lines;

- the Bloem versions have a much more irregular flow between five and twelve syllable alexandrines; there are no rhymes.

- punctuation: the frequent use of enjambed lines in verse that pauses in mid line or includes questions offers rhythmical pointers for oral delivery;

- the elements: the Heaney poetry is placed predominantly on or under the ground, close to or in water; Bloem’s favoured element is air; fire is provided by the subtext of firing pots in the kiln

- the vocabulary of 1 reflects Heaney’s knowledge of technical botanical and geological issues plus insights into the chemicals and substances associated with glazing and firing pots; reference to light (phosphor, luminous) adds to the mythologized, otherworldly picture of the young potter;

- a distant chiasmus: imagination creates a mythology surrounding a goddess Ceramica and her kingdom; the lines reverse the order (grass, glass, ash(a+b+c in line 20) ash-pits, shards and chlorophylls(c+b+a in line 39)

- Bloem’s versions are to do with natural light and enlightenment the first set in a narrower historical and geographical window (2i); 2ii expands into much wider spheres: tides, omnipresent and so on

- epigraph and 1 are anchored in the past; Bloem is reporting a series of present moments and the implications emanating from them;

- addition of suffix y creates adjectives from nouns on 4 occasion;

- there is use of simile and personification but imagery is broadly theme-bound;

- Heaney is a meticulous craftsman using combinations of vowel and consonant to form a poem that is something to be listened to.

- the music of the poem: fourteen assonant strands are woven into the text; Heaney places them grouped within specific areas to create internal rhymes , or reprises them at intervals or threads them through the text:

- Alliterative consonant effects allow pulses or beats or soothings or hissings or frictions of consonant sound to modify the assonant melodies:

- the epigraph of Dutch Potter, for example, is strong in alveolar nasals and sibilants alongside bi-labial and velar plosives; it is well worth teasing out the sound clusters for yourself if only to admire the poet’s sonic engineering:

- Consonants (with their phonetic symbols) can be classed according to where in the mouth they occur

- Front-of-mouth sounds:

voiceless bi-labial plosive [p] voiced bi-labial plosive [b]; voiceless labio-dental fricative [f] voiced labio-dental fricative [v]; bi-labial nasal [m]; bilabial continuant [w]

- Behind-the-teeth sounds:

voiceless alveolar plosive [t] voiced alveolar plosive [d]; voiceless alveolar fricative as in church match [tʃ]; voiced alveolar fricative as in judge age [dʒ]; voiceless dental fricative [θ] as in thin path; voiced dental fricative as in this other [ð]; voiceless alveolar fricative [s] voiced alveolar fricative [z]; continuant [h] alveolar nasal [n] alveolar approximant [l]; alveolar trill [r]; dental ‘y’ [j] as in yet

- Rear-of-mouth sounds:

voiceless velar plosive [k] voiced velar plosive [g]; voiceless post-alveolar fricative [ʃ] as in ship sure, voiced post- alveolar fricative [ʒ] as in pleasure; palatal nasal [ŋ] as in ring/ anger.

Thank you for shedding light on the vocabulary within the poem. I learned a good deal from this essay